|

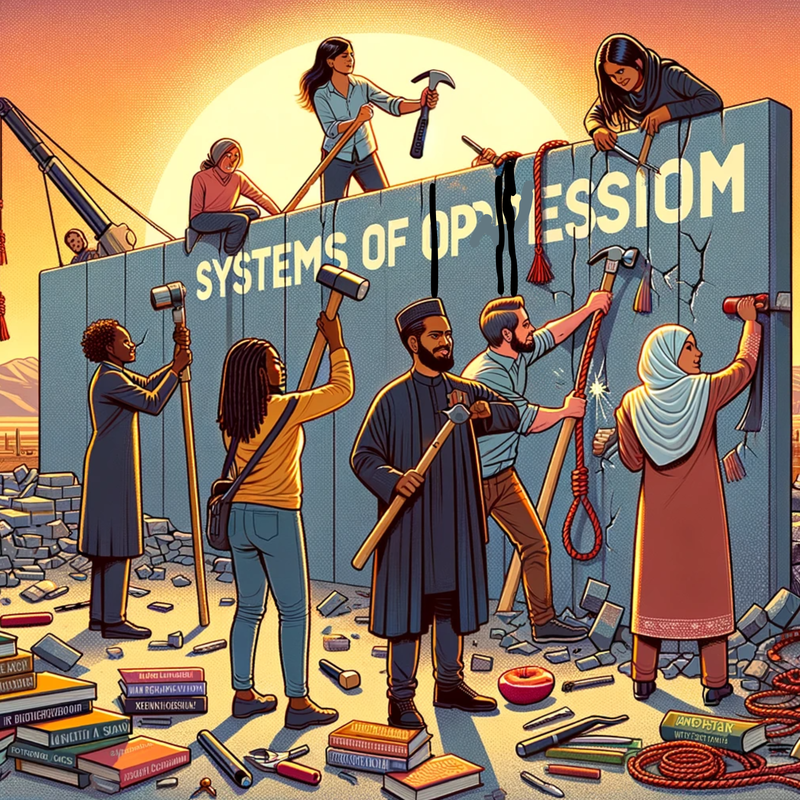

In today's world, being an ally has become essential to supporting under-resourced communities and fostering inclusivity. However, not all allyship is created equal. Understanding the nuances of allyship is crucial for creating real change and dismantling systemic inequalities. In this article we will explore the three levels of allyship: Actor, Ally, and Accomplice, highlighting the differences between each and why they matter.

2. Informed and Coordinated Actions with Impacted Communities: One distinguishing characteristic of Accomplices is their humility and commitment to learning from and coordinating with the communities most affected by systemic oppression. They recognize that those who directly experience racism, colonization, and White supremacy are the experts in their own lived experiences. Accomplices prioritize listening to these voices, amplifying their concerns, and taking action in alignment with their goals and strategies. 3. Understanding Interconnected Freedoms and Liberations: Accomplices understand that justice and liberation are interconnected. They recognize that dismantling oppressive systems benefits everyone, including themselves. They reject the idea that one group's liberation comes at the expense of another's. Instead, they understand that true freedom is bound together and that dismantling systemic oppression is essential for a just and equitable society. Accomplices actively work towards creating a world where everyone can thrive without discrimination or harm. 4.0No Retreat or Withdrawal: Accomplices are steadfast in their commitment. They do not back down or retreat when faced with challenges or pushback from oppressive structures. They understand that the fight for justice is neither easy nor comfortable. They persistently engage in confrontations, uncomfortable conversations, and actions that disrupt the status quo. For them, retreat is not an option, as they are driven by a deep sense of moral responsibility to create a more equitable world.Accomplice-level allyship is not for the faint of heart. It demands courage, self-awareness, humility, and an unwavering commitment to justice. Accomplices recognize that they are part of a broader movement for social change and that their actions can have a lasting impact on dismantling the deeply rooted systems of oppression. In a world where systemic injustice persists, Accomplice-level allies serve as beacons of hope, lighting the way for a more just and equitable future for all. Key Characteristics:

Conclusion

Understanding the three levels of allyship – Actor, Ally, and Accomplice – is crucial for anyone aiming to support oppressed and underrepresented communities effectively. While Actor-level allies may serve as a starting point for many, the ultimate goal should be to progress towards Accomplice-level allyship. By actively educating themselves, challenging oppressive systems, and working alongside oppressed and underrepresented communities, individuals can contribute to creating a more equitable and inclusive society. Allyship is not a destination; it's a continuous journey towards justice and equality. “Avalanche Lake Hike with Off-road Wheelchair 12” by GlacierNPS (2016). Like most things in our world, the travel industry has historically left many people behind. From outdoor recreation companies only showing white, able-bodied individuals in their ads to travel companies and bloggers ignoring the accessibility concerns of certain trips, there’s a lot to address. So where does one start?

This blog post will offer a couple of inclusivity-focused tips for those involved in the travel industry. If we truly want all kinds of people to explore outdoor spaces or book exciting trips around the country/world, we need to ensure that these destinations actually welcome individuals of various backgrounds. Diversity itself is important, but we need to take the next step and make travel inclusive. 1. Disclose Important Accessibility Information One of the largest groups excluded from travel experiences is the disabled community. Ideally, every space should be created with a range of body types and ability levels in mind, but the unfortunate reality is that many spaces aren’t disability-friendly at all. However, one thing travel companies and content creators can do now is explicitly describe a space’s physical environment for potential travelers. Some basic questions to consider: Is the ground level? Are there inclines or steps? How big is the overall space? How wide are the pathways throughout the space? Are the pathways composed of dirt, gravel, or something else? Are there any specific accessibility features that have been included, such as boardwalks or ramps? Of course, these are only a few of many possibilities, as each space will be different, but answers to questions like these will help form a clear picture of the space being explored. Such information is important to disclose because it will signal to individuals whether or not they can access, or feel comfortable within, a certain outdoor space or travel experience. If, for example, a wheelchair user goes on a hike thinking the trail is accessible but discovers along the way that there are several steps to ascend, that’s a problem—one that could have easily been addressed had folks known ahead of time just what they might encounter on said hike. Accompanying this information should be several pictures that provide a comprehensive look at what somebody might see on the trip. This isn’t for aesthetic reasons but, rather, providing a way for potential travelers to visualize themselves in the space being pictured. If you’re a travel blogger taking cute pictures of the trip anyway, then it shouldn’t take much extra effort to document the physical environment you’re engaging with. A word of caution: When sharing this information, don’t assume a space is accessible simply because the ground is level or there’s a ramp for wheelchair users. The disabled community isn’t a monolith. As such, describing the space itself rather than making a judgment about it will go a lot further in helping potential travelers access it. Overall, information is power. If universal design still has a long way to go in terms of being implemented throughout our country (and the world), then the least someone should be able to do is decide for themselves, with all the information available, if a trip is worthwhile. We need to rethink spaces and make them accessible to all, yes, but in the meantime, we can pay our information forward. 2. Consider the Safety of Marginalized Travelers It’s easy to simply say that a space welcomes everybody regardless of identity, but the reality is that too many spaces feature very few people from marginalized backgrounds. This is especially true for outdoor spaces. For this tip, it might be helpful to more specifically think about inclusion over diversity. For example, many BIPOC individuals engage in outdoor recreation, but if you work for a travel company that’s advertising a certain outdoors activity in an area that’s mostly trafficked by white people, it wouldn’t be wise to suggest just how “comfortable” or “welcome” a person of color would feel in said area. This advertising tactic screams of “diversity on the books” without actually making sure that marginalized individuals are included in the activity or within the space in general. Ultimately, inclusion in this sense boils down to safety. Not being welcome or comfortable in a space might translate into being insulted, followed, or even physically assaulted. Accordingly, in addition to accessibility information, travel companies and content creators should disclose any safety concerns about certain trips or spaces. Some basic questions to consider: Do BIPOC, queer, disabled, and/or other marginalized individuals often travel to this space? Have travelers from one (or more) of these historically disenfranchised groups written about this place? How conservative are the surrounding areas? Questions like these will help individuals of different groups determine how comfortable they'd be should they embark on a certain travel experience. Like accessibility, safety for marginalized groups isn’t something that’s going to be worked into every space overnight. Changing the culture of our country, specifically within the travel industry, will take time. For now, though, a queer person or BIPOC individual shouldn’t have to go digging to determine if they’d feel safe on a specific hike—that information should be readily available. Follow Inclusive Guide on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about inclusive travel. “Bridalveil Fall—Yosemite National Park” by Jorge Láscar (2017). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. In his famous documentary, Ken Burns called national parks “America’s best idea.” When individuals think of the United States, they often conjure images of wilderness in the American West documented by Burns, such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. These spaces, which have been preserved through the National Park System, are associated with environmentalists like Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, the latter of whom founded the Oakland-based environmental justice organization Sierra Club. To think of Yellowstone, for example, is to think of America itself.

But behind this grand narrative of conservation is a complicated racial history, one dotted with segregation, prejudice, and white privilege. During the Jim Crow era, national parks adhered to the “separate but equal” laws throughout the country, meaning outdoor spaces in the South and within border states such as Kentucky and Missouri were treated like segregated businesses. The park rangers who oversaw these spaces upheld segregation in campgrounds, restrooms, parking lots, cabins, and other public facilities. While some National Park Service employees desired to treat visitors equally, these officials were usually challenged throughout Jim Crow states by park superintendents, Southern congressmen, and various organizations. Even when governmental officials were sympathetic to the concerns of Black citizens, the actions and policies carried out often didn’t reflect a pro-Black sentiment for fear of upsetting white people with power. For instance, Harold Ickes, a known supporter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who held the position of Secretary of the Interior between 1933–1946, opposed marking facilities as “segregated” on maps, even if there was segregation in practice, so as to not perpetuate the idea of separation throughout the national parks. This idea may have seemed good in theory, but Ickes’ decision effectively made it more difficult for potential Black visitors to discern which spaces were safe for them. In the absence of word-of-mouth insights from fellow Black travelers, Black families would have to risk using a public resource, such as a picnic table or a bathroom, to ultimately determine if they were allowed to use it. Another questionable policy was upheld by the third director of the National Park Service, Arno Cammerer. He only wanted to build public facilities for Black visitors if there was sufficient demand for them. However, this policy didn’t apply to white individuals, and because of the perceived low interest in outdoor recreation from Black folks, facilities often weren’t built for Black use. And of the facilities that were created specifically for Black visitors, they were generally deprioritized, underfunded, and/or simply subpar compared to those built for white people. These historical accounts of Ickes and Cammerer represent only a fraction of the racist practices and attitudes that prevailed throughout the National Park System during the Jim Crow era. A couple of other distressing truths: Virginia’s Colonial National Historical Park was completely developed using segregated Black labor, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which was responsible for the development of various trails and park facilities, would segregate their workers across Southern parks. Even big names like Muir and Teddy Roosevelt are fraught with racism, as the former made derogatory remarks about Black and Indigenous folks and the latter viewed Filipinos, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans as inferior to Americans. Ostensibly bastions of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy, as Burns’ documentary might present them, national parks have been anything but. Two years ago, the Sierra Club’s executive director even called out the organization’s founder, the “father of national parks,” for his racism. On top of all this, Indigenous peoples have been forced off their homelands in the name of national park preservation. One of the earliest national parks, Yosemite bears a history of bloodshed as the Miwok people were exterminated and, if any settlements remained afterward, were evicted from their land. And even if Indigenous peoples weren’t murdered or relocated, they were denied access to national park resources, which they’d used for many years before the areas were deemed “national parks.” Unfortunately, the problematic history of the National Park System follows us to today. Inclusive Guide Co-founder Parker McMullen Bushman was recently denied entry at a California park by a worker there who thought she was going to do something “nefarious.” Although this particular area was open to the public 24 hours a day, Parker was racially profiled by the park official and subsequently treated unfairly. In Colorado, too, Black women have been harassed by park employees. Indeed, a group of Black women was recently stopped by a ranger at Rocky Mountain National Park because they were thought to be smoking weed, but they didn’t have any cannabis on them. These are only a couple of the many stories that exist for people of color at national parks across the US. Like any business, national parks aren’t neutral spaces. They contain human beings with the potential to discriminate, treat people unfairly, and maintain the status quo. National parks are only as welcoming as the people who oversee them. As such, park rangers and other staff should be aware of the biases they may bring to their management of parks and other wilderness areas. Segregation is no longer the law of the land, but like Parker’s experiences reveal, outdoor spaces aren’t free from microaggressions, prejudice, and unwelcoming attitudes in general. If we want everybody to use and benefit from national parks, we must manage them intentionally with an eye toward equity, inclusion, and social justice. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @kweenwerk and @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about the history of outdoor spaces. Sources Colchester, Marcus. “Conservation Policy and Indigenous Peoples.” Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, March 2004, culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/conservation-policy-and-indigenous-peoples#:~:text=National%20parks%2C%20pioneered%20in%20the,central%20to%20conservation%20policy%20worldwide. Accessed 15 June 2022. Conde, Arturo. “Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘racist’ and ‘progressive’ legacy, historian says, is part of monument debate.” NBC News, 20 July 2020, nbcnews.com/news/latino/teddy-roosevelt-s-racist-progressive-legacy-historian-says-part-monument-n1234163. Accessed 15 June 2022. Melley, Brian. “Sierra Club calls out founder John Muir for racist views.” PBS Newshour, 22 July 2020, pbs.org/newshour/nation/sierra-club-calls-out-founder-john-muir-for-racist-views. Accessed 15 June 2022. “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” PBS, pbs.org/kenburns/the-national-parks/. Accessed 15 June 2022. Repanshek, Kurt. “How the National Park Service Grappled with Segregation During the 20th Century.” National Parks Traveler, 18 Aug. 2019, nationalparkstraveler.org/2019/08/how-national-park-service-grappled-segregation-during-20th-century. Accessed 15 June 2022. |

KWEEN WERK NARRATIVESKWEEN stands for Keep Widening Environmental Engagement Narratives. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed