|

“Avalanche Lake Hike with Off-road Wheelchair 12” by GlacierNPS (2016). Like most things in our world, the travel industry has historically left many people behind. From outdoor recreation companies only showing white, able-bodied individuals in their ads to travel companies and bloggers ignoring the accessibility concerns of certain trips, there’s a lot to address. So where does one start?

This blog post will offer a couple of inclusivity-focused tips for those involved in the travel industry. If we truly want all kinds of people to explore outdoor spaces or book exciting trips around the country/world, we need to ensure that these destinations actually welcome individuals of various backgrounds. Diversity itself is important, but we need to take the next step and make travel inclusive. 1. Disclose Important Accessibility Information One of the largest groups excluded from travel experiences is the disabled community. Ideally, every space should be created with a range of body types and ability levels in mind, but the unfortunate reality is that many spaces aren’t disability-friendly at all. However, one thing travel companies and content creators can do now is explicitly describe a space’s physical environment for potential travelers. Some basic questions to consider: Is the ground level? Are there inclines or steps? How big is the overall space? How wide are the pathways throughout the space? Are the pathways composed of dirt, gravel, or something else? Are there any specific accessibility features that have been included, such as boardwalks or ramps? Of course, these are only a few of many possibilities, as each space will be different, but answers to questions like these will help form a clear picture of the space being explored. Such information is important to disclose because it will signal to individuals whether or not they can access, or feel comfortable within, a certain outdoor space or travel experience. If, for example, a wheelchair user goes on a hike thinking the trail is accessible but discovers along the way that there are several steps to ascend, that’s a problem—one that could have easily been addressed had folks known ahead of time just what they might encounter on said hike. Accompanying this information should be several pictures that provide a comprehensive look at what somebody might see on the trip. This isn’t for aesthetic reasons but, rather, providing a way for potential travelers to visualize themselves in the space being pictured. If you’re a travel blogger taking cute pictures of the trip anyway, then it shouldn’t take much extra effort to document the physical environment you’re engaging with. A word of caution: When sharing this information, don’t assume a space is accessible simply because the ground is level or there’s a ramp for wheelchair users. The disabled community isn’t a monolith. As such, describing the space itself rather than making a judgment about it will go a lot further in helping potential travelers access it. Overall, information is power. If universal design still has a long way to go in terms of being implemented throughout our country (and the world), then the least someone should be able to do is decide for themselves, with all the information available, if a trip is worthwhile. We need to rethink spaces and make them accessible to all, yes, but in the meantime, we can pay our information forward. 2. Consider the Safety of Marginalized Travelers It’s easy to simply say that a space welcomes everybody regardless of identity, but the reality is that too many spaces feature very few people from marginalized backgrounds. This is especially true for outdoor spaces. For this tip, it might be helpful to more specifically think about inclusion over diversity. For example, many BIPOC individuals engage in outdoor recreation, but if you work for a travel company that’s advertising a certain outdoors activity in an area that’s mostly trafficked by white people, it wouldn’t be wise to suggest just how “comfortable” or “welcome” a person of color would feel in said area. This advertising tactic screams of “diversity on the books” without actually making sure that marginalized individuals are included in the activity or within the space in general. Ultimately, inclusion in this sense boils down to safety. Not being welcome or comfortable in a space might translate into being insulted, followed, or even physically assaulted. Accordingly, in addition to accessibility information, travel companies and content creators should disclose any safety concerns about certain trips or spaces. Some basic questions to consider: Do BIPOC, queer, disabled, and/or other marginalized individuals often travel to this space? Have travelers from one (or more) of these historically disenfranchised groups written about this place? How conservative are the surrounding areas? Questions like these will help individuals of different groups determine how comfortable they'd be should they embark on a certain travel experience. Like accessibility, safety for marginalized groups isn’t something that’s going to be worked into every space overnight. Changing the culture of our country, specifically within the travel industry, will take time. For now, though, a queer person or BIPOC individual shouldn’t have to go digging to determine if they’d feel safe on a specific hike—that information should be readily available. Follow Inclusive Guide on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about inclusive travel. Most of you have probably heard of DWB: “driving while Black.” This term refers to the difficulties faced specifically by Black drivers, including being yelled at by highway patrol officers, being forced into random vehicle searches, or worse—being physically assaulted due to racial profiling. Unfortunately, DWB extends to other types of personal transportation in America, such as RVs. RVing may be considered a quintessential American pastime—images of the “great American road trip” come to mind—but this activity has risks for BIPOC, especially Black families.

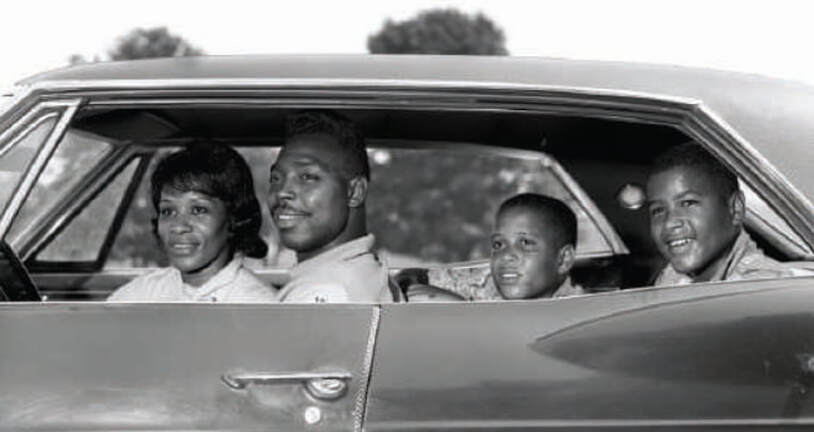

As you know, Inclusive Guide's co-founder Parker is on a road trip across the American South and Midwest with her mixed-race family to raise visibility for BIPOC travel and outdoor recreation. However, things aren’t magically discrimination-free in 2022 for Parker’s family or other BIPOC families. When on a road trip today, there’s a high likelihood families will pass through predominantly white communities full of conservative residents with their Trump signs still up; in fact, this was one of the first things Parker encountered on her journey. Even if nothing happens when passing through these towns, the mere anxiety of mentally preparing for a list of what-ifs puts strain on those traveling, especially the parents of children of color. Moreover, as we discussed in earlier blog posts, sundown towns were in full force in certain areas until the 1970s, and national parks that were located in segregated parts of the country during Jim Crow upheld the local “separate but equal” policies, thereby making outdoor recreation less safe for Black families. American road trips, whether as the mythology we see satirized in National Lampoon or the practical, lived experience of them, are overwhelmingly white. Some Black men from the South remember hearing the story of “the Bogeyman in the woods” growing up, which was often code for “the KKK will get you.” While a lot has changed for the better since the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, these childhood stories stick with people. You don’t simply forget the racism you’ve experienced—and that you’ve been taught to be wary of—because businesses are legally obligated to say they don’t discriminate based on race. Racism lives on, however insidiously. Fortunately, there are groups trying to make activities like RVing more welcoming and comfortable for Black individuals. The National African American RVers’ Association, for instance, is one organization that’s on a mission to connect Black RVers and their families around the US. While many Black people have been discouraged from outdoor recreation because of a lack of representation and inclusion within the travel industry, a history of racism in the outdoors, and other legitimate concerns, there does exist a community of Black outdoor enthusiasts. You may not see a Black family hitting the road on the latest RV ad, but there are many Black and mixed-race families, such as Parker’s, enjoying this American dream—you just have to pay attention. So what can you do to help make Black individuals feel more comfortable RVing or engaging in outdoor recreation? If you work for a national park or interpretation service, you could reflect on and update your educational content to ensure that it doesn’t tell history from a “white victor” perspective, thus allowing BIPOC to be a more significant part of the narrative. If you’re an outdoor recreation retailer, you could represent BIPOC in your advertising and even team up with folks like KWEEN WERK to encourage more people of color to enjoy the outdoors. Or if you’re a fellow RVer, you could simply check yourself and your privilege when interacting with travelers of color on the road or at campgrounds. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about outdoor recreation for BIPOC. Sources Dixon, Nanci. “Where are all the Black RVers? Why the outdoors isn’t as inclusive as you think.” RVtravel, 15 Oct. 2020, rvtravel.com/blackrvers970. Accessed 29 June 2022. “National African American RVers’ Association.” NAARVA, naarva.com. Accessed 29 June 2022. Parker here. I’m excited to share that this summer, my family and I are taking a two-week road trip through the American South and Midwest. We’re leaving Denver June 23 and will be driving down to Georgia and up through Michigan, all the way back to Colorado on July 10. I look forward to showing my three kids some of my favorite places and outdoor recreation areas along our path, such as Savannah and Tybee Island on the Georgia coast. While RVing across the country with your mixed-race family doesn’t seem like the most radical thing to do in 2022, safe and easy travel hasn’t always been the case for Black and brown folks. As I prepare for my family’s trip, I can’t help but think about the charged history of Black travel, including the spread of sundown towns, the Green Book, and all the other hoops people had to jump through in order to experience the “American dream” of vacations—because what isn’t more American than road-tripping? I’ve lovingly titled my family’s journey “The Liberation Tour” because it hasn’t been that long in American history since a family like mine could safely realize this dream. Travel and outdoor recreation are historically white pastimes; not too long ago, whenever people of color wanted to participate in these activities, they needed to take extra precautions. Sundown towns—or white communities that have intentionally kept out Black people, often taking extralegal measures to terrorize and even kill those who remained past sunset—have only fell out of favor since the 1970s. To this day, there could still be unofficial sundown towns around the country, especially in communities that are mostly white. Colorado is home to more than 10 official sundown towns and over a dozen more that are “unlisted,” many of which are about an hour outside the Denver metro area, such as Burlington, Longmont, and Loveland. Within the last year, certain residents in one of the cities listed opposed measures that could have elevated the voices of its marginalized members in legislative decision-making. Many of the racist ideologies that cemented sundown towns of the midcentury still hold true today. Racism has no lane and knows no boundaries.

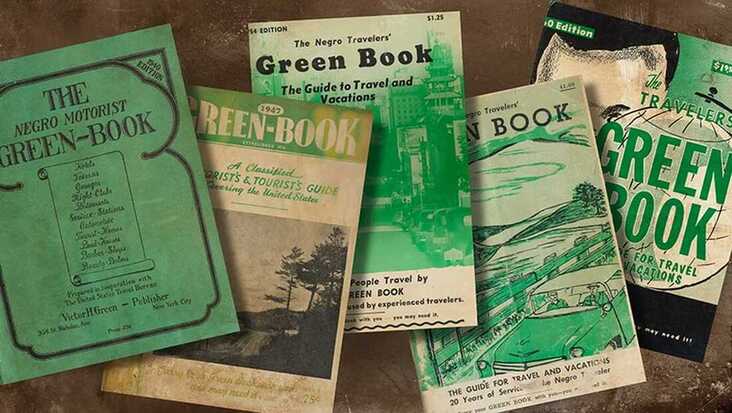

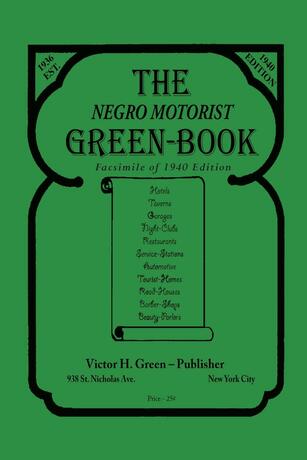

Enter The Negro Motorist Green Book. I’ve said this before, but I see my colleagues’ and my work at Inclusive Guide as taking the Green Book into the 21st century. Safety issues for travelers from marginalized communities persist to this very day. Before I discuss the need for resources like the Green Book today, I want to highlight a bit of the book’s history and why it was important. This guide was an essential tool for Black travelers in America. In fact, the inside cover of the Green Book stated, “Never Leave Home Without It.” It listed safe and welcoming spaces for Black travelers to visit between the years 1936–1966, with the ’66–’67 edition being the last issue printed, just after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. The credit for the original Green Book goes to Victor and Alma Green, alongside a Black, all-female editorial staff. Victor was a postal worker in Harlem. He asked everyone he knew to spread the word and send him postcards or letters about the safe places Black people could stay around the country. Like I mentioned earlier, many of the rules of segregated travel weren’t obviously posted. Because navigating Black travel was incredibly dangerous and unpredictable, the Green Book filled the safety gap and provided a comprehensive (yet ever-growing) list of all the safe places for Black motorists across the United States. One important Green Book site in the Denver area was Lincoln Hills. Founded in 1922 by E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt about an hour outside downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was one of the only Black resorts in the US during the 1920s. Individuals could buy 25 x 100 ft. lots at the resort, which they could then use to build summer cottages. Approximately 470 lots were sold by 1928. While the Great Depression financially prevented many Black families from realizing their summer-vacation dreams in the Colorado outdoors, lot owners still used their land as campsites or for day trips in the decades to come. You also didn’t need to own property at Lincoln Hills to take advantage of its offerings, including educational camps for Black girls and outdoor recreation activities. Plus, Black travelers were always welcome to stay at Winks Lodge, where they could eat home-cooked meals, enjoy a good cocktail, and listen to performances by talented Black musicians or writers. The passage of the Civil Rights Act may have made places like Lincoln Hills obsolete, but discrimination didn’t automatically end for travelers with one piece of legislation. Driving while Black remains a concern practically everywhere in the US. Some predominantly white communities act hostile toward travelers of color. And even if you might not be physically harmed in certain places, you’re still at risk of experiencing microaggressions and emotional or psychological abuse. The parallels between then and now are clear for people of color—the world still isn’t safe for us, nor is it safe for LGBTQ+, disabled, and other marginalized folks. Take my own family, for instance. While traveling, we’ve been stared at, questioned, and followed just for existing in certain places, especially throughout the South. Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case that banned laws prohibiting interracial marriage, may have been passed in 1967, but from my own experiences living in the world as part of a mixed-race family, I can tell you that some people still don’t like to see a white man and a Black woman together. Although I can take the heat, I don’t want my kids to experience this discrimination—and they shouldn’t have to in the first place. All this is why we need resources like Inclusive Guide to help travelers navigate the messy world of oppression. There’s a disconnect between our country’s official nondiscrimination laws and the unofficial discriminatory behavior that actually occurs. People still need to know which spaces are welcoming and which ones might be uncomfortable for them to be in, and this information can only be known through lived experience. Like the network of Black travelers that made the Green Book possible, those of us at the margins of society must share our insights and support one another. It’s time for us to reclaim travel. Beyond using Inclusive Guide, you can join and support organizations such as The Unpopular Black and Black Girls Travel Too that seek to make travel more accessible and fun for specific groups of people traditionally left out of the American travel narrative. In these two examples, Black individuals are being centered when, for far too long, we’ve been excluded from both outdoor spaces and the general notion of “adventure.” There are too many affinity groups and resources to list here (that’s a good thing!), so I encourage you to find a group that speaks to you, but some of the organizations I support are Blackpackers, Fat Girls Hiking, Latino Outdoors, Native Women’s Wilderness, and Muslim Hikers. There’s a space for you no matter what your identity is.

In the meantime, check out Inclusive Guide’s social media and blog, as well as all of KWEEN WERK’s channels, to follow me on my Liberation Tour throughout the South and Midwest. We’ll be sharing educational posts and videos related to Black travel over the course of my two-week trip. I also plan on using Inclusive Guide in real time so that you can see and learn about some of the inclusive places I visit. While this trip is ultimately a bonding experience for my family—and some well-deserved R&R for myself—I hope my journey increases the visibility of Black people in outdoor spaces and the world of travel more broadly. We be trippin’, y’all—we always have been. If you’ve been wanting to embark on an adventure but are worried that you won’t belong or that it isn’t for you, let me be the first to say that you 100%, absolutely can. Traveling is for everybody—and we’re taking it back. |

KWEEN WERK NARRATIVESKWEEN stands for Keep Widening Environmental Engagement Narratives. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed