|

McIntosh County Shouters. Darien, GA, 19 Jan. 2020. For the past week, the amazing co-founder of Inclusive Guide Parker and her family have been taking on their all-American cross-country road trip. As they hike, camp, and explore the great outdoors, in a way, they’re also time-traveling through U.S. history. Some stops are active timestamps, marking the distance between our past and present, as well as providing guidance and insight into a possible future. This week, our co-founder will be traveling back to Georgia and South Carolina to reconnect with their Gullah heritage.

The Gullah/Geechee people are descendants of enslaved Central and West Africans who were brought to the Sea Island plantations of the lower Atlantic coastline in the 1700s. Researchers designate the region from Sandy Island, SC, to Amelia Island, FL, as the Gullah Coast. However, the Gullah/Geechee are said to span as far north as the Virginia/North Carolina border. This unique culture has been linked to specific ethnic groups that are indigenous to West and Central Africa, bringing with them a rich heritage of cultural traditions. The geography and climate of the southeastern coast often brought disease to captors and enslavers, especially as they introduced new enslaved Africans to shore. Research states that “West Africans were far more able to cope with the climatic conditions found in the South.” As a result, some islands were completely left to the care and management of enslaved Gullah/Geechee people. This isolation brought a sense of relative autonomy to the enslaved people of the region, allowing them to retain much of their African heritage and, subsequently, develop a new, beautiful Gullah/Geechee culture. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Gullah” is the accepted name of the islanders in South Carolina, while “Geechee” refers to the islanders of Georgia. Anthropologists and historians speculate that both “Gullah” and “Geechee” are borrowed words from a number of ethnic groups such as the Gola, Kissi, Mende, Temne, Twi, and Vai peoples, all of which contributed to the subsequent “creolization” of the southeastern coastal culture in the U.S. The Gullah/Geechee also developed their own language, a form of creole mixed with the languages of West and Central African ethnic groups, as well as from their enslavers. According to the Gullah/Geechee Corridor, the Gullah/Geechee language is the only African creole language in the U.S. and has since deeply influenced Southern vernacular. The fact that hundreds of thousands of Gullah/Geechee remain in these marshlands and coastal islands doesn’t mean that they didn’t attempt to escape enslavement. Between the American Revolution and the Reconstruction Era, thousands of enslaved laborers from the Gullah/Geechee region gained their freedom by escaping to Nova Scotia. Self-emancipated Africans who were once harbored by the Spanish formed an alliance with Native American refugees in Florida,forming the Seminole Nation. Parker shares a story that her family told her about their great-great-grandmother and father (who was a baby at the time) who were being pursued by slave catchers. She talks about how the group was so afraid of being captured and taken back that they suggested killing the crying baby to avoid getting caught. Her family determined that if they killed the baby, the mother wouldn’t have survived. Instead, she sat under a bush, nursing the baby and trying to keep quiet until danger passed. There’s a huge possibility that our co-founder Parker might not be here had their elders gone through with this suggestion. This is not a statement of “pro-life,” however; this is a powerful testament to the terror of chattel slavery and the grave cost of the pursuit of freedom. Though originally brought as slaves to what is now part of the Gullah/Geechee region, Parker’s family has lived on James Island in South Carolina for hundreds of years. As she reconnects with her Gullah heritage, we keep in mind that many of the beliefs that substantiated the mass genocide of Indigenous peoples of the First Nations and the trans-Atlantic slave trade are the foundation of socioeconomic structures today. In order to truly change the world as we know it, we must take this knowledge with us and act. Stand up for Black and Indigenous rights in your own communities. Support legislation to tackle discrimination at the highest level. Donate to nonprofits and other groups trying to make a difference. One small way you can help is by supporting Inclusive Guide and the work we’re doing to address systemic racism and, more specifically, discrimination against Black and Indigenous communities. Using the Guide itself is a step in the right direction, but if you have the resources, we encourage you to contribute to our GoFundMe campaign so that we may continue the work of racial justice: https://www.gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. “Bridalveil Fall—Yosemite National Park” by Jorge Láscar (2017). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. In his famous documentary, Ken Burns called national parks “America’s best idea.” When individuals think of the United States, they often conjure images of wilderness in the American West documented by Burns, such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. These spaces, which have been preserved through the National Park System, are associated with environmentalists like Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, the latter of whom founded the Oakland-based environmental justice organization Sierra Club. To think of Yellowstone, for example, is to think of America itself.

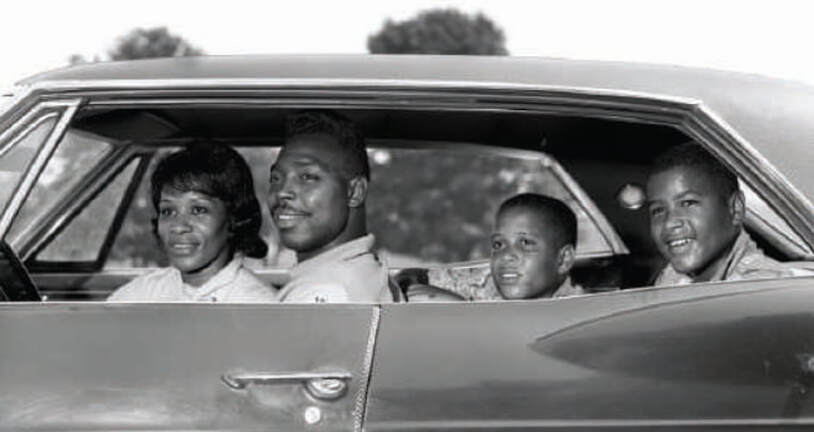

But behind this grand narrative of conservation is a complicated racial history, one dotted with segregation, prejudice, and white privilege. During the Jim Crow era, national parks adhered to the “separate but equal” laws throughout the country, meaning outdoor spaces in the South and within border states such as Kentucky and Missouri were treated like segregated businesses. The park rangers who oversaw these spaces upheld segregation in campgrounds, restrooms, parking lots, cabins, and other public facilities. While some National Park Service employees desired to treat visitors equally, these officials were usually challenged throughout Jim Crow states by park superintendents, Southern congressmen, and various organizations. Even when governmental officials were sympathetic to the concerns of Black citizens, the actions and policies carried out often didn’t reflect a pro-Black sentiment for fear of upsetting white people with power. For instance, Harold Ickes, a known supporter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who held the position of Secretary of the Interior between 1933–1946, opposed marking facilities as “segregated” on maps, even if there was segregation in practice, so as to not perpetuate the idea of separation throughout the national parks. This idea may have seemed good in theory, but Ickes’ decision effectively made it more difficult for potential Black visitors to discern which spaces were safe for them. In the absence of word-of-mouth insights from fellow Black travelers, Black families would have to risk using a public resource, such as a picnic table or a bathroom, to ultimately determine if they were allowed to use it. Another questionable policy was upheld by the third director of the National Park Service, Arno Cammerer. He only wanted to build public facilities for Black visitors if there was sufficient demand for them. However, this policy didn’t apply to white individuals, and because of the perceived low interest in outdoor recreation from Black folks, facilities often weren’t built for Black use. And of the facilities that were created specifically for Black visitors, they were generally deprioritized, underfunded, and/or simply subpar compared to those built for white people. These historical accounts of Ickes and Cammerer represent only a fraction of the racist practices and attitudes that prevailed throughout the National Park System during the Jim Crow era. A couple of other distressing truths: Virginia’s Colonial National Historical Park was completely developed using segregated Black labor, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which was responsible for the development of various trails and park facilities, would segregate their workers across Southern parks. Even big names like Muir and Teddy Roosevelt are fraught with racism, as the former made derogatory remarks about Black and Indigenous folks and the latter viewed Filipinos, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans as inferior to Americans. Ostensibly bastions of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy, as Burns’ documentary might present them, national parks have been anything but. Two years ago, the Sierra Club’s executive director even called out the organization’s founder, the “father of national parks,” for his racism. On top of all this, Indigenous peoples have been forced off their homelands in the name of national park preservation. One of the earliest national parks, Yosemite bears a history of bloodshed as the Miwok people were exterminated and, if any settlements remained afterward, were evicted from their land. And even if Indigenous peoples weren’t murdered or relocated, they were denied access to national park resources, which they’d used for many years before the areas were deemed “national parks.” Unfortunately, the problematic history of the National Park System follows us to today. Inclusive Guide Co-founder Parker McMullen Bushman was recently denied entry at a California park by a worker there who thought she was going to do something “nefarious.” Although this particular area was open to the public 24 hours a day, Parker was racially profiled by the park official and subsequently treated unfairly. In Colorado, too, Black women have been harassed by park employees. Indeed, a group of Black women was recently stopped by a ranger at Rocky Mountain National Park because they were thought to be smoking weed, but they didn’t have any cannabis on them. These are only a couple of the many stories that exist for people of color at national parks across the US. Like any business, national parks aren’t neutral spaces. They contain human beings with the potential to discriminate, treat people unfairly, and maintain the status quo. National parks are only as welcoming as the people who oversee them. As such, park rangers and other staff should be aware of the biases they may bring to their management of parks and other wilderness areas. Segregation is no longer the law of the land, but like Parker’s experiences reveal, outdoor spaces aren’t free from microaggressions, prejudice, and unwelcoming attitudes in general. If we want everybody to use and benefit from national parks, we must manage them intentionally with an eye toward equity, inclusion, and social justice. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @kweenwerk and @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about the history of outdoor spaces. Sources Colchester, Marcus. “Conservation Policy and Indigenous Peoples.” Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, March 2004, culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/conservation-policy-and-indigenous-peoples#:~:text=National%20parks%2C%20pioneered%20in%20the,central%20to%20conservation%20policy%20worldwide. Accessed 15 June 2022. Conde, Arturo. “Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘racist’ and ‘progressive’ legacy, historian says, is part of monument debate.” NBC News, 20 July 2020, nbcnews.com/news/latino/teddy-roosevelt-s-racist-progressive-legacy-historian-says-part-monument-n1234163. Accessed 15 June 2022. Melley, Brian. “Sierra Club calls out founder John Muir for racist views.” PBS Newshour, 22 July 2020, pbs.org/newshour/nation/sierra-club-calls-out-founder-john-muir-for-racist-views. Accessed 15 June 2022. “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” PBS, pbs.org/kenburns/the-national-parks/. Accessed 15 June 2022. Repanshek, Kurt. “How the National Park Service Grappled with Segregation During the 20th Century.” National Parks Traveler, 18 Aug. 2019, nationalparkstraveler.org/2019/08/how-national-park-service-grappled-segregation-during-20th-century. Accessed 15 June 2022. As you probably know, our co-founder Parker is on a road trip through the American South and Midwest. Her journey is a testament to how far we’ve come as a country—a Black woman with her white husband and mixed-race kids in an RV is, fortunately, no longer an automatic invitation for violence. However, people of color still face many challenges when it comes to travel, and not all spaces are safe, despite all the nondiscrimination laws on the books. That’s why we created Inclusive Guide and why we must continue the fight for equity and justice for all.

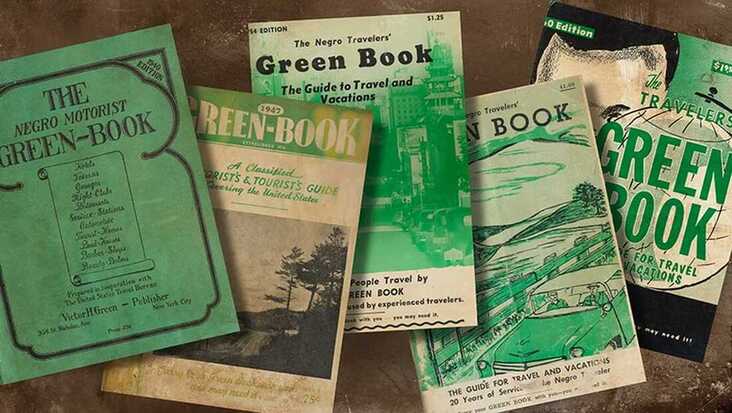

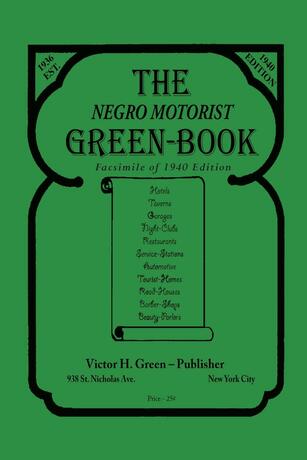

Not too long ago—as recent as the 1970s, in fact—there existed blatantly racist areas throughout the country known as sundown towns. These all-white communities would display obvious signage telling Black travelers to stay out after sunset—or else. If Black travelers were spotted in a sundown town after dark, the community’s residents would often take extralegal measures, including verbal, psychological, and/or physical violence, to oust them. Black individuals were not only terrorized but also murdered in sundown towns. Various sundown towns existed across the South, but what some don’t know is that these racist communities could be found all around the United States. Oftentimes, there were more sundown towns in historically “free” states compared to their Southern neighbors. While some of these areas in the Midwest or West might not have labeled themselves as “sundown towns,” the fact remains that plenty of places across the country were hostile to Black individuals, even after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (And to no surprise, several of these former sundown towns remain predominantly white, sometimes upwards of 80 or 90 percent.) Moreover, sundown towns would intentionally exclude other people of color and historically marginalized groups. Prohibitions existed for not only Black individuals but also people of Chinese, Japanese, Native American, or Jewish descent, among others. Because of these discriminatory practices, traveling long distances by car was difficult for BIPOC individuals, making resources like The Negro Motorist Green Book necessary for travelers. The scary part of this history is that, well, sundown towns aren’t entirely a feature of our country’s past. These areas and attitudes persist into the 21st century but with more subtle tactics at individuals’ disposal to keep Black people out. BIPOC folks have time and again experienced discrimination in predominantly white communities—this is simply a fact. While such racism may manifest itself as a microaggression, such as an insensitive joke about Black people and culture or an uneducated comment about colorblindness, or as something more dangerous like yelling, stalking, or fighting, what ultimately ties these experiences together is a commitment to white supremacy. To unlearn white supremacy, we must know our racist past (and present). Confronting the reality of sundown towns and other deeply racist aspects of US history is only the first step, however. Educating oneself is significant, but we must also actively combat the white-supremacist systems that have been embedded within the fabric of our country. We believe that Inclusive Guide is one part of the solution, yes, but even more important is tackling policy at the highest level to ensure everybody feels safe, welcome, and celebrated no matter where they are. Whether it’s at the local coffee shop or a national park, people of all identities deserve to be comfortable being themselves. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about BIPOC travel. Sources Coen, Ross. “Sundown Towns.” BlackPast, 23 Aug. 2020, blackpast.org/african-american-history/sundown-towns/. Accessed 1 June 2022. “Historical Database of Sundown Towns.” History and Social Justice, justice.tougaloo.edu/sundown-towns/using-the-sundown-towns-database/state-map/. Accessed 1 June 2022. Parker here. I’m excited to share that this summer, my family and I are taking a two-week road trip through the American South and Midwest. We’re leaving Denver June 23 and will be driving down to Georgia and up through Michigan, all the way back to Colorado on July 10. I look forward to showing my three kids some of my favorite places and outdoor recreation areas along our path, such as Savannah and Tybee Island on the Georgia coast. While RVing across the country with your mixed-race family doesn’t seem like the most radical thing to do in 2022, safe and easy travel hasn’t always been the case for Black and brown folks. As I prepare for my family’s trip, I can’t help but think about the charged history of Black travel, including the spread of sundown towns, the Green Book, and all the other hoops people had to jump through in order to experience the “American dream” of vacations—because what isn’t more American than road-tripping? I’ve lovingly titled my family’s journey “The Liberation Tour” because it hasn’t been that long in American history since a family like mine could safely realize this dream. Travel and outdoor recreation are historically white pastimes; not too long ago, whenever people of color wanted to participate in these activities, they needed to take extra precautions. Sundown towns—or white communities that have intentionally kept out Black people, often taking extralegal measures to terrorize and even kill those who remained past sunset—have only fell out of favor since the 1970s. To this day, there could still be unofficial sundown towns around the country, especially in communities that are mostly white. Colorado is home to more than 10 official sundown towns and over a dozen more that are “unlisted,” many of which are about an hour outside the Denver metro area, such as Burlington, Longmont, and Loveland. Within the last year, certain residents in one of the cities listed opposed measures that could have elevated the voices of its marginalized members in legislative decision-making. Many of the racist ideologies that cemented sundown towns of the midcentury still hold true today. Racism has no lane and knows no boundaries.

Enter The Negro Motorist Green Book. I’ve said this before, but I see my colleagues’ and my work at Inclusive Guide as taking the Green Book into the 21st century. Safety issues for travelers from marginalized communities persist to this very day. Before I discuss the need for resources like the Green Book today, I want to highlight a bit of the book’s history and why it was important. This guide was an essential tool for Black travelers in America. In fact, the inside cover of the Green Book stated, “Never Leave Home Without It.” It listed safe and welcoming spaces for Black travelers to visit between the years 1936–1966, with the ’66–’67 edition being the last issue printed, just after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. The credit for the original Green Book goes to Victor and Alma Green, alongside a Black, all-female editorial staff. Victor was a postal worker in Harlem. He asked everyone he knew to spread the word and send him postcards or letters about the safe places Black people could stay around the country. Like I mentioned earlier, many of the rules of segregated travel weren’t obviously posted. Because navigating Black travel was incredibly dangerous and unpredictable, the Green Book filled the safety gap and provided a comprehensive (yet ever-growing) list of all the safe places for Black motorists across the United States. One important Green Book site in the Denver area was Lincoln Hills. Founded in 1922 by E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt about an hour outside downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was one of the only Black resorts in the US during the 1920s. Individuals could buy 25 x 100 ft. lots at the resort, which they could then use to build summer cottages. Approximately 470 lots were sold by 1928. While the Great Depression financially prevented many Black families from realizing their summer-vacation dreams in the Colorado outdoors, lot owners still used their land as campsites or for day trips in the decades to come. You also didn’t need to own property at Lincoln Hills to take advantage of its offerings, including educational camps for Black girls and outdoor recreation activities. Plus, Black travelers were always welcome to stay at Winks Lodge, where they could eat home-cooked meals, enjoy a good cocktail, and listen to performances by talented Black musicians or writers. The passage of the Civil Rights Act may have made places like Lincoln Hills obsolete, but discrimination didn’t automatically end for travelers with one piece of legislation. Driving while Black remains a concern practically everywhere in the US. Some predominantly white communities act hostile toward travelers of color. And even if you might not be physically harmed in certain places, you’re still at risk of experiencing microaggressions and emotional or psychological abuse. The parallels between then and now are clear for people of color—the world still isn’t safe for us, nor is it safe for LGBTQ+, disabled, and other marginalized folks. Take my own family, for instance. While traveling, we’ve been stared at, questioned, and followed just for existing in certain places, especially throughout the South. Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case that banned laws prohibiting interracial marriage, may have been passed in 1967, but from my own experiences living in the world as part of a mixed-race family, I can tell you that some people still don’t like to see a white man and a Black woman together. Although I can take the heat, I don’t want my kids to experience this discrimination—and they shouldn’t have to in the first place. All this is why we need resources like Inclusive Guide to help travelers navigate the messy world of oppression. There’s a disconnect between our country’s official nondiscrimination laws and the unofficial discriminatory behavior that actually occurs. People still need to know which spaces are welcoming and which ones might be uncomfortable for them to be in, and this information can only be known through lived experience. Like the network of Black travelers that made the Green Book possible, those of us at the margins of society must share our insights and support one another. It’s time for us to reclaim travel. Beyond using Inclusive Guide, you can join and support organizations such as The Unpopular Black and Black Girls Travel Too that seek to make travel more accessible and fun for specific groups of people traditionally left out of the American travel narrative. In these two examples, Black individuals are being centered when, for far too long, we’ve been excluded from both outdoor spaces and the general notion of “adventure.” There are too many affinity groups and resources to list here (that’s a good thing!), so I encourage you to find a group that speaks to you, but some of the organizations I support are Blackpackers, Fat Girls Hiking, Latino Outdoors, Native Women’s Wilderness, and Muslim Hikers. There’s a space for you no matter what your identity is.

In the meantime, check out Inclusive Guide’s social media and blog, as well as all of KWEEN WERK’s channels, to follow me on my Liberation Tour throughout the South and Midwest. We’ll be sharing educational posts and videos related to Black travel over the course of my two-week trip. I also plan on using Inclusive Guide in real time so that you can see and learn about some of the inclusive places I visit. While this trip is ultimately a bonding experience for my family—and some well-deserved R&R for myself—I hope my journey increases the visibility of Black people in outdoor spaces and the world of travel more broadly. We be trippin’, y’all—we always have been. If you’ve been wanting to embark on an adventure but are worried that you won’t belong or that it isn’t for you, let me be the first to say that you 100%, absolutely can. Traveling is for everybody—and we’re taking it back. |

KWEEN WERK NARRATIVESKWEEN stands for Keep Widening Environmental Engagement Narratives. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed