|

In today's world, being an ally has become essential to supporting under-resourced communities and fostering inclusivity. However, not all allyship is created equal. Understanding the nuances of allyship is crucial for creating real change and dismantling systemic inequalities. In this article we will explore the three levels of allyship: Actor, Ally, and Accomplice, highlighting the differences between each and why they matter.

2. Informed and Coordinated Actions with Impacted Communities: One distinguishing characteristic of Accomplices is their humility and commitment to learning from and coordinating with the communities most affected by systemic oppression. They recognize that those who directly experience racism, colonization, and White supremacy are the experts in their own lived experiences. Accomplices prioritize listening to these voices, amplifying their concerns, and taking action in alignment with their goals and strategies. 3. Understanding Interconnected Freedoms and Liberations: Accomplices understand that justice and liberation are interconnected. They recognize that dismantling oppressive systems benefits everyone, including themselves. They reject the idea that one group's liberation comes at the expense of another's. Instead, they understand that true freedom is bound together and that dismantling systemic oppression is essential for a just and equitable society. Accomplices actively work towards creating a world where everyone can thrive without discrimination or harm. 4.0No Retreat or Withdrawal: Accomplices are steadfast in their commitment. They do not back down or retreat when faced with challenges or pushback from oppressive structures. They understand that the fight for justice is neither easy nor comfortable. They persistently engage in confrontations, uncomfortable conversations, and actions that disrupt the status quo. For them, retreat is not an option, as they are driven by a deep sense of moral responsibility to create a more equitable world.Accomplice-level allyship is not for the faint of heart. It demands courage, self-awareness, humility, and an unwavering commitment to justice. Accomplices recognize that they are part of a broader movement for social change and that their actions can have a lasting impact on dismantling the deeply rooted systems of oppression. In a world where systemic injustice persists, Accomplice-level allies serve as beacons of hope, lighting the way for a more just and equitable future for all. Key Characteristics:

Conclusion

Understanding the three levels of allyship – Actor, Ally, and Accomplice – is crucial for anyone aiming to support oppressed and underrepresented communities effectively. While Actor-level allies may serve as a starting point for many, the ultimate goal should be to progress towards Accomplice-level allyship. By actively educating themselves, challenging oppressive systems, and working alongside oppressed and underrepresented communities, individuals can contribute to creating a more equitable and inclusive society. Allyship is not a destination; it's a continuous journey towards justice and equality. “Avalanche Lake Hike with Off-road Wheelchair 12” by GlacierNPS (2016). Like most things in our world, the travel industry has historically left many people behind. From outdoor recreation companies only showing white, able-bodied individuals in their ads to travel companies and bloggers ignoring the accessibility concerns of certain trips, there’s a lot to address. So where does one start?

This blog post will offer a couple of inclusivity-focused tips for those involved in the travel industry. If we truly want all kinds of people to explore outdoor spaces or book exciting trips around the country/world, we need to ensure that these destinations actually welcome individuals of various backgrounds. Diversity itself is important, but we need to take the next step and make travel inclusive. 1. Disclose Important Accessibility Information One of the largest groups excluded from travel experiences is the disabled community. Ideally, every space should be created with a range of body types and ability levels in mind, but the unfortunate reality is that many spaces aren’t disability-friendly at all. However, one thing travel companies and content creators can do now is explicitly describe a space’s physical environment for potential travelers. Some basic questions to consider: Is the ground level? Are there inclines or steps? How big is the overall space? How wide are the pathways throughout the space? Are the pathways composed of dirt, gravel, or something else? Are there any specific accessibility features that have been included, such as boardwalks or ramps? Of course, these are only a few of many possibilities, as each space will be different, but answers to questions like these will help form a clear picture of the space being explored. Such information is important to disclose because it will signal to individuals whether or not they can access, or feel comfortable within, a certain outdoor space or travel experience. If, for example, a wheelchair user goes on a hike thinking the trail is accessible but discovers along the way that there are several steps to ascend, that’s a problem—one that could have easily been addressed had folks known ahead of time just what they might encounter on said hike. Accompanying this information should be several pictures that provide a comprehensive look at what somebody might see on the trip. This isn’t for aesthetic reasons but, rather, providing a way for potential travelers to visualize themselves in the space being pictured. If you’re a travel blogger taking cute pictures of the trip anyway, then it shouldn’t take much extra effort to document the physical environment you’re engaging with. A word of caution: When sharing this information, don’t assume a space is accessible simply because the ground is level or there’s a ramp for wheelchair users. The disabled community isn’t a monolith. As such, describing the space itself rather than making a judgment about it will go a lot further in helping potential travelers access it. Overall, information is power. If universal design still has a long way to go in terms of being implemented throughout our country (and the world), then the least someone should be able to do is decide for themselves, with all the information available, if a trip is worthwhile. We need to rethink spaces and make them accessible to all, yes, but in the meantime, we can pay our information forward. 2. Consider the Safety of Marginalized Travelers It’s easy to simply say that a space welcomes everybody regardless of identity, but the reality is that too many spaces feature very few people from marginalized backgrounds. This is especially true for outdoor spaces. For this tip, it might be helpful to more specifically think about inclusion over diversity. For example, many BIPOC individuals engage in outdoor recreation, but if you work for a travel company that’s advertising a certain outdoors activity in an area that’s mostly trafficked by white people, it wouldn’t be wise to suggest just how “comfortable” or “welcome” a person of color would feel in said area. This advertising tactic screams of “diversity on the books” without actually making sure that marginalized individuals are included in the activity or within the space in general. Ultimately, inclusion in this sense boils down to safety. Not being welcome or comfortable in a space might translate into being insulted, followed, or even physically assaulted. Accordingly, in addition to accessibility information, travel companies and content creators should disclose any safety concerns about certain trips or spaces. Some basic questions to consider: Do BIPOC, queer, disabled, and/or other marginalized individuals often travel to this space? Have travelers from one (or more) of these historically disenfranchised groups written about this place? How conservative are the surrounding areas? Questions like these will help individuals of different groups determine how comfortable they'd be should they embark on a certain travel experience. Like accessibility, safety for marginalized groups isn’t something that’s going to be worked into every space overnight. Changing the culture of our country, specifically within the travel industry, will take time. For now, though, a queer person or BIPOC individual shouldn’t have to go digging to determine if they’d feel safe on a specific hike—that information should be readily available. Follow Inclusive Guide on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about inclusive travel. McIntosh County Shouters. Darien, GA, 19 Jan. 2020. For the past week, the amazing co-founder of Inclusive Guide Parker and her family have been taking on their all-American cross-country road trip. As they hike, camp, and explore the great outdoors, in a way, they’re also time-traveling through U.S. history. Some stops are active timestamps, marking the distance between our past and present, as well as providing guidance and insight into a possible future. This week, our co-founder will be traveling back to Georgia and South Carolina to reconnect with their Gullah heritage.

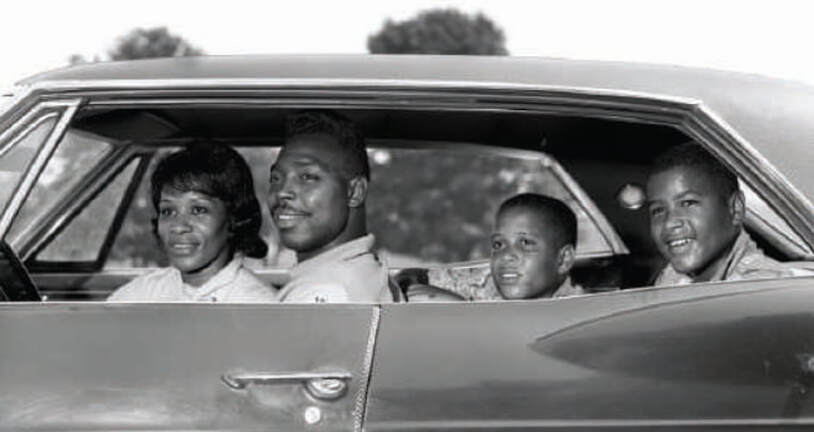

The Gullah/Geechee people are descendants of enslaved Central and West Africans who were brought to the Sea Island plantations of the lower Atlantic coastline in the 1700s. Researchers designate the region from Sandy Island, SC, to Amelia Island, FL, as the Gullah Coast. However, the Gullah/Geechee are said to span as far north as the Virginia/North Carolina border. This unique culture has been linked to specific ethnic groups that are indigenous to West and Central Africa, bringing with them a rich heritage of cultural traditions. The geography and climate of the southeastern coast often brought disease to captors and enslavers, especially as they introduced new enslaved Africans to shore. Research states that “West Africans were far more able to cope with the climatic conditions found in the South.” As a result, some islands were completely left to the care and management of enslaved Gullah/Geechee people. This isolation brought a sense of relative autonomy to the enslaved people of the region, allowing them to retain much of their African heritage and, subsequently, develop a new, beautiful Gullah/Geechee culture. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Gullah” is the accepted name of the islanders in South Carolina, while “Geechee” refers to the islanders of Georgia. Anthropologists and historians speculate that both “Gullah” and “Geechee” are borrowed words from a number of ethnic groups such as the Gola, Kissi, Mende, Temne, Twi, and Vai peoples, all of which contributed to the subsequent “creolization” of the southeastern coastal culture in the U.S. The Gullah/Geechee also developed their own language, a form of creole mixed with the languages of West and Central African ethnic groups, as well as from their enslavers. According to the Gullah/Geechee Corridor, the Gullah/Geechee language is the only African creole language in the U.S. and has since deeply influenced Southern vernacular. The fact that hundreds of thousands of Gullah/Geechee remain in these marshlands and coastal islands doesn’t mean that they didn’t attempt to escape enslavement. Between the American Revolution and the Reconstruction Era, thousands of enslaved laborers from the Gullah/Geechee region gained their freedom by escaping to Nova Scotia. Self-emancipated Africans who were once harbored by the Spanish formed an alliance with Native American refugees in Florida,forming the Seminole Nation. Parker shares a story that her family told her about their great-great-grandmother and father (who was a baby at the time) who were being pursued by slave catchers. She talks about how the group was so afraid of being captured and taken back that they suggested killing the crying baby to avoid getting caught. Her family determined that if they killed the baby, the mother wouldn’t have survived. Instead, she sat under a bush, nursing the baby and trying to keep quiet until danger passed. There’s a huge possibility that our co-founder Parker might not be here had their elders gone through with this suggestion. This is not a statement of “pro-life,” however; this is a powerful testament to the terror of chattel slavery and the grave cost of the pursuit of freedom. Though originally brought as slaves to what is now part of the Gullah/Geechee region, Parker’s family has lived on James Island in South Carolina for hundreds of years. As she reconnects with her Gullah heritage, we keep in mind that many of the beliefs that substantiated the mass genocide of Indigenous peoples of the First Nations and the trans-Atlantic slave trade are the foundation of socioeconomic structures today. In order to truly change the world as we know it, we must take this knowledge with us and act. Stand up for Black and Indigenous rights in your own communities. Support legislation to tackle discrimination at the highest level. Donate to nonprofits and other groups trying to make a difference. One small way you can help is by supporting Inclusive Guide and the work we’re doing to address systemic racism and, more specifically, discrimination against Black and Indigenous communities. Using the Guide itself is a step in the right direction, but if you have the resources, we encourage you to contribute to our GoFundMe campaign so that we may continue the work of racial justice: https://www.gofundme.com/f/digital-green-book-website. Most of you have probably heard of DWB: “driving while Black.” This term refers to the difficulties faced specifically by Black drivers, including being yelled at by highway patrol officers, being forced into random vehicle searches, or worse—being physically assaulted due to racial profiling. Unfortunately, DWB extends to other types of personal transportation in America, such as RVs. RVing may be considered a quintessential American pastime—images of the “great American road trip” come to mind—but this activity has risks for BIPOC, especially Black families.

As you know, Inclusive Guide's co-founder Parker is on a road trip across the American South and Midwest with her mixed-race family to raise visibility for BIPOC travel and outdoor recreation. However, things aren’t magically discrimination-free in 2022 for Parker’s family or other BIPOC families. When on a road trip today, there’s a high likelihood families will pass through predominantly white communities full of conservative residents with their Trump signs still up; in fact, this was one of the first things Parker encountered on her journey. Even if nothing happens when passing through these towns, the mere anxiety of mentally preparing for a list of what-ifs puts strain on those traveling, especially the parents of children of color. Moreover, as we discussed in earlier blog posts, sundown towns were in full force in certain areas until the 1970s, and national parks that were located in segregated parts of the country during Jim Crow upheld the local “separate but equal” policies, thereby making outdoor recreation less safe for Black families. American road trips, whether as the mythology we see satirized in National Lampoon or the practical, lived experience of them, are overwhelmingly white. Some Black men from the South remember hearing the story of “the Bogeyman in the woods” growing up, which was often code for “the KKK will get you.” While a lot has changed for the better since the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, these childhood stories stick with people. You don’t simply forget the racism you’ve experienced—and that you’ve been taught to be wary of—because businesses are legally obligated to say they don’t discriminate based on race. Racism lives on, however insidiously. Fortunately, there are groups trying to make activities like RVing more welcoming and comfortable for Black individuals. The National African American RVers’ Association, for instance, is one organization that’s on a mission to connect Black RVers and their families around the US. While many Black people have been discouraged from outdoor recreation because of a lack of representation and inclusion within the travel industry, a history of racism in the outdoors, and other legitimate concerns, there does exist a community of Black outdoor enthusiasts. You may not see a Black family hitting the road on the latest RV ad, but there are many Black and mixed-race families, such as Parker’s, enjoying this American dream—you just have to pay attention. So what can you do to help make Black individuals feel more comfortable RVing or engaging in outdoor recreation? If you work for a national park or interpretation service, you could reflect on and update your educational content to ensure that it doesn’t tell history from a “white victor” perspective, thus allowing BIPOC to be a more significant part of the narrative. If you’re an outdoor recreation retailer, you could represent BIPOC in your advertising and even team up with folks like KWEEN WERK to encourage more people of color to enjoy the outdoors. Or if you’re a fellow RVer, you could simply check yourself and your privilege when interacting with travelers of color on the road or at campgrounds. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about outdoor recreation for BIPOC. Sources Dixon, Nanci. “Where are all the Black RVers? Why the outdoors isn’t as inclusive as you think.” RVtravel, 15 Oct. 2020, rvtravel.com/blackrvers970. Accessed 29 June 2022. “National African American RVers’ Association.” NAARVA, naarva.com. Accessed 29 June 2022. “Bridalveil Fall—Yosemite National Park” by Jorge Láscar (2017). Licensed under CC BY 2.0. In his famous documentary, Ken Burns called national parks “America’s best idea.” When individuals think of the United States, they often conjure images of wilderness in the American West documented by Burns, such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. These spaces, which have been preserved through the National Park System, are associated with environmentalists like Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, the latter of whom founded the Oakland-based environmental justice organization Sierra Club. To think of Yellowstone, for example, is to think of America itself.

But behind this grand narrative of conservation is a complicated racial history, one dotted with segregation, prejudice, and white privilege. During the Jim Crow era, national parks adhered to the “separate but equal” laws throughout the country, meaning outdoor spaces in the South and within border states such as Kentucky and Missouri were treated like segregated businesses. The park rangers who oversaw these spaces upheld segregation in campgrounds, restrooms, parking lots, cabins, and other public facilities. While some National Park Service employees desired to treat visitors equally, these officials were usually challenged throughout Jim Crow states by park superintendents, Southern congressmen, and various organizations. Even when governmental officials were sympathetic to the concerns of Black citizens, the actions and policies carried out often didn’t reflect a pro-Black sentiment for fear of upsetting white people with power. For instance, Harold Ickes, a known supporter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who held the position of Secretary of the Interior between 1933–1946, opposed marking facilities as “segregated” on maps, even if there was segregation in practice, so as to not perpetuate the idea of separation throughout the national parks. This idea may have seemed good in theory, but Ickes’ decision effectively made it more difficult for potential Black visitors to discern which spaces were safe for them. In the absence of word-of-mouth insights from fellow Black travelers, Black families would have to risk using a public resource, such as a picnic table or a bathroom, to ultimately determine if they were allowed to use it. Another questionable policy was upheld by the third director of the National Park Service, Arno Cammerer. He only wanted to build public facilities for Black visitors if there was sufficient demand for them. However, this policy didn’t apply to white individuals, and because of the perceived low interest in outdoor recreation from Black folks, facilities often weren’t built for Black use. And of the facilities that were created specifically for Black visitors, they were generally deprioritized, underfunded, and/or simply subpar compared to those built for white people. These historical accounts of Ickes and Cammerer represent only a fraction of the racist practices and attitudes that prevailed throughout the National Park System during the Jim Crow era. A couple of other distressing truths: Virginia’s Colonial National Historical Park was completely developed using segregated Black labor, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which was responsible for the development of various trails and park facilities, would segregate their workers across Southern parks. Even big names like Muir and Teddy Roosevelt are fraught with racism, as the former made derogatory remarks about Black and Indigenous folks and the latter viewed Filipinos, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans as inferior to Americans. Ostensibly bastions of freedom, egalitarianism, and democracy, as Burns’ documentary might present them, national parks have been anything but. Two years ago, the Sierra Club’s executive director even called out the organization’s founder, the “father of national parks,” for his racism. On top of all this, Indigenous peoples have been forced off their homelands in the name of national park preservation. One of the earliest national parks, Yosemite bears a history of bloodshed as the Miwok people were exterminated and, if any settlements remained afterward, were evicted from their land. And even if Indigenous peoples weren’t murdered or relocated, they were denied access to national park resources, which they’d used for many years before the areas were deemed “national parks.” Unfortunately, the problematic history of the National Park System follows us to today. Inclusive Guide Co-founder Parker McMullen Bushman was recently denied entry at a California park by a worker there who thought she was going to do something “nefarious.” Although this particular area was open to the public 24 hours a day, Parker was racially profiled by the park official and subsequently treated unfairly. In Colorado, too, Black women have been harassed by park employees. Indeed, a group of Black women was recently stopped by a ranger at Rocky Mountain National Park because they were thought to be smoking weed, but they didn’t have any cannabis on them. These are only a couple of the many stories that exist for people of color at national parks across the US. Like any business, national parks aren’t neutral spaces. They contain human beings with the potential to discriminate, treat people unfairly, and maintain the status quo. National parks are only as welcoming as the people who oversee them. As such, park rangers and other staff should be aware of the biases they may bring to their management of parks and other wilderness areas. Segregation is no longer the law of the land, but like Parker’s experiences reveal, outdoor spaces aren’t free from microaggressions, prejudice, and unwelcoming attitudes in general. If we want everybody to use and benefit from national parks, we must manage them intentionally with an eye toward equity, inclusion, and social justice. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @kweenwerk and @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about the history of outdoor spaces. Sources Colchester, Marcus. “Conservation Policy and Indigenous Peoples.” Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, March 2004, culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/conservation-policy-and-indigenous-peoples#:~:text=National%20parks%2C%20pioneered%20in%20the,central%20to%20conservation%20policy%20worldwide. Accessed 15 June 2022. Conde, Arturo. “Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘racist’ and ‘progressive’ legacy, historian says, is part of monument debate.” NBC News, 20 July 2020, nbcnews.com/news/latino/teddy-roosevelt-s-racist-progressive-legacy-historian-says-part-monument-n1234163. Accessed 15 June 2022. Melley, Brian. “Sierra Club calls out founder John Muir for racist views.” PBS Newshour, 22 July 2020, pbs.org/newshour/nation/sierra-club-calls-out-founder-john-muir-for-racist-views. Accessed 15 June 2022. “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” PBS, pbs.org/kenburns/the-national-parks/. Accessed 15 June 2022. Repanshek, Kurt. “How the National Park Service Grappled with Segregation During the 20th Century.” National Parks Traveler, 18 Aug. 2019, nationalparkstraveler.org/2019/08/how-national-park-service-grappled-segregation-during-20th-century. Accessed 15 June 2022. As you probably know, our co-founder Parker is on a road trip through the American South and Midwest. Her journey is a testament to how far we’ve come as a country—a Black woman with her white husband and mixed-race kids in an RV is, fortunately, no longer an automatic invitation for violence. However, people of color still face many challenges when it comes to travel, and not all spaces are safe, despite all the nondiscrimination laws on the books. That’s why we created Inclusive Guide and why we must continue the fight for equity and justice for all.

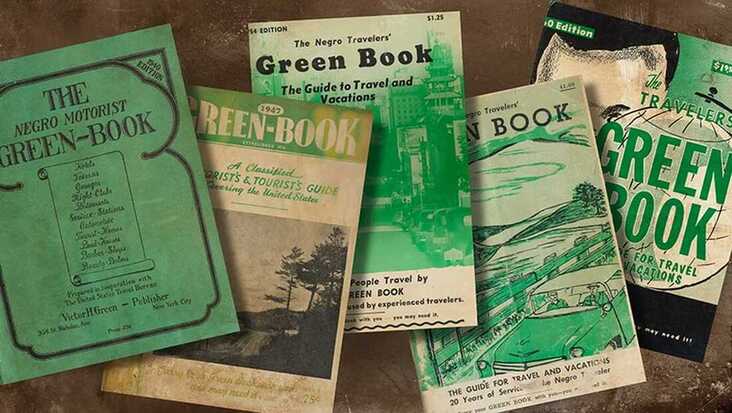

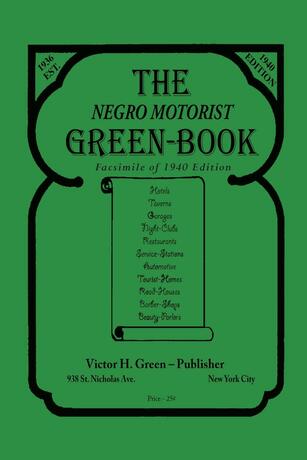

Not too long ago—as recent as the 1970s, in fact—there existed blatantly racist areas throughout the country known as sundown towns. These all-white communities would display obvious signage telling Black travelers to stay out after sunset—or else. If Black travelers were spotted in a sundown town after dark, the community’s residents would often take extralegal measures, including verbal, psychological, and/or physical violence, to oust them. Black individuals were not only terrorized but also murdered in sundown towns. Various sundown towns existed across the South, but what some don’t know is that these racist communities could be found all around the United States. Oftentimes, there were more sundown towns in historically “free” states compared to their Southern neighbors. While some of these areas in the Midwest or West might not have labeled themselves as “sundown towns,” the fact remains that plenty of places across the country were hostile to Black individuals, even after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (And to no surprise, several of these former sundown towns remain predominantly white, sometimes upwards of 80 or 90 percent.) Moreover, sundown towns would intentionally exclude other people of color and historically marginalized groups. Prohibitions existed for not only Black individuals but also people of Chinese, Japanese, Native American, or Jewish descent, among others. Because of these discriminatory practices, traveling long distances by car was difficult for BIPOC individuals, making resources like The Negro Motorist Green Book necessary for travelers. The scary part of this history is that, well, sundown towns aren’t entirely a feature of our country’s past. These areas and attitudes persist into the 21st century but with more subtle tactics at individuals’ disposal to keep Black people out. BIPOC folks have time and again experienced discrimination in predominantly white communities—this is simply a fact. While such racism may manifest itself as a microaggression, such as an insensitive joke about Black people and culture or an uneducated comment about colorblindness, or as something more dangerous like yelling, stalking, or fighting, what ultimately ties these experiences together is a commitment to white supremacy. To unlearn white supremacy, we must know our racist past (and present). Confronting the reality of sundown towns and other deeply racist aspects of US history is only the first step, however. Educating oneself is significant, but we must also actively combat the white-supremacist systems that have been embedded within the fabric of our country. We believe that Inclusive Guide is one part of the solution, yes, but even more important is tackling policy at the highest level to ensure everybody feels safe, welcome, and celebrated no matter where they are. Whether it’s at the local coffee shop or a national park, people of all identities deserve to be comfortable being themselves. Follow us on Twitter @InclusiveGuide, Instagram @inclusiveguide, and Facebook @InclusiveJourneys to stay up to date with Parker’s Liberation Tour across the South and Midwest. You’ll also want to follow along to catch more educational posts and insights like this about BIPOC travel. Sources Coen, Ross. “Sundown Towns.” BlackPast, 23 Aug. 2020, blackpast.org/african-american-history/sundown-towns/. Accessed 1 June 2022. “Historical Database of Sundown Towns.” History and Social Justice, justice.tougaloo.edu/sundown-towns/using-the-sundown-towns-database/state-map/. Accessed 1 June 2022. Parker here. I’m excited to share that this summer, my family and I are taking a two-week road trip through the American South and Midwest. We’re leaving Denver June 23 and will be driving down to Georgia and up through Michigan, all the way back to Colorado on July 10. I look forward to showing my three kids some of my favorite places and outdoor recreation areas along our path, such as Savannah and Tybee Island on the Georgia coast. While RVing across the country with your mixed-race family doesn’t seem like the most radical thing to do in 2022, safe and easy travel hasn’t always been the case for Black and brown folks. As I prepare for my family’s trip, I can’t help but think about the charged history of Black travel, including the spread of sundown towns, the Green Book, and all the other hoops people had to jump through in order to experience the “American dream” of vacations—because what isn’t more American than road-tripping? I’ve lovingly titled my family’s journey “The Liberation Tour” because it hasn’t been that long in American history since a family like mine could safely realize this dream. Travel and outdoor recreation are historically white pastimes; not too long ago, whenever people of color wanted to participate in these activities, they needed to take extra precautions. Sundown towns—or white communities that have intentionally kept out Black people, often taking extralegal measures to terrorize and even kill those who remained past sunset—have only fell out of favor since the 1970s. To this day, there could still be unofficial sundown towns around the country, especially in communities that are mostly white. Colorado is home to more than 10 official sundown towns and over a dozen more that are “unlisted,” many of which are about an hour outside the Denver metro area, such as Burlington, Longmont, and Loveland. Within the last year, certain residents in one of the cities listed opposed measures that could have elevated the voices of its marginalized members in legislative decision-making. Many of the racist ideologies that cemented sundown towns of the midcentury still hold true today. Racism has no lane and knows no boundaries.

Enter The Negro Motorist Green Book. I’ve said this before, but I see my colleagues’ and my work at Inclusive Guide as taking the Green Book into the 21st century. Safety issues for travelers from marginalized communities persist to this very day. Before I discuss the need for resources like the Green Book today, I want to highlight a bit of the book’s history and why it was important. This guide was an essential tool for Black travelers in America. In fact, the inside cover of the Green Book stated, “Never Leave Home Without It.” It listed safe and welcoming spaces for Black travelers to visit between the years 1936–1966, with the ’66–’67 edition being the last issue printed, just after the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed. The credit for the original Green Book goes to Victor and Alma Green, alongside a Black, all-female editorial staff. Victor was a postal worker in Harlem. He asked everyone he knew to spread the word and send him postcards or letters about the safe places Black people could stay around the country. Like I mentioned earlier, many of the rules of segregated travel weren’t obviously posted. Because navigating Black travel was incredibly dangerous and unpredictable, the Green Book filled the safety gap and provided a comprehensive (yet ever-growing) list of all the safe places for Black motorists across the United States. One important Green Book site in the Denver area was Lincoln Hills. Founded in 1922 by E. C. Regnier and Roger E. Ewalt about an hour outside downtown Denver, Lincoln Hills was one of the only Black resorts in the US during the 1920s. Individuals could buy 25 x 100 ft. lots at the resort, which they could then use to build summer cottages. Approximately 470 lots were sold by 1928. While the Great Depression financially prevented many Black families from realizing their summer-vacation dreams in the Colorado outdoors, lot owners still used their land as campsites or for day trips in the decades to come. You also didn’t need to own property at Lincoln Hills to take advantage of its offerings, including educational camps for Black girls and outdoor recreation activities. Plus, Black travelers were always welcome to stay at Winks Lodge, where they could eat home-cooked meals, enjoy a good cocktail, and listen to performances by talented Black musicians or writers. The passage of the Civil Rights Act may have made places like Lincoln Hills obsolete, but discrimination didn’t automatically end for travelers with one piece of legislation. Driving while Black remains a concern practically everywhere in the US. Some predominantly white communities act hostile toward travelers of color. And even if you might not be physically harmed in certain places, you’re still at risk of experiencing microaggressions and emotional or psychological abuse. The parallels between then and now are clear for people of color—the world still isn’t safe for us, nor is it safe for LGBTQ+, disabled, and other marginalized folks. Take my own family, for instance. While traveling, we’ve been stared at, questioned, and followed just for existing in certain places, especially throughout the South. Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case that banned laws prohibiting interracial marriage, may have been passed in 1967, but from my own experiences living in the world as part of a mixed-race family, I can tell you that some people still don’t like to see a white man and a Black woman together. Although I can take the heat, I don’t want my kids to experience this discrimination—and they shouldn’t have to in the first place. All this is why we need resources like Inclusive Guide to help travelers navigate the messy world of oppression. There’s a disconnect between our country’s official nondiscrimination laws and the unofficial discriminatory behavior that actually occurs. People still need to know which spaces are welcoming and which ones might be uncomfortable for them to be in, and this information can only be known through lived experience. Like the network of Black travelers that made the Green Book possible, those of us at the margins of society must share our insights and support one another. It’s time for us to reclaim travel. Beyond using Inclusive Guide, you can join and support organizations such as The Unpopular Black and Black Girls Travel Too that seek to make travel more accessible and fun for specific groups of people traditionally left out of the American travel narrative. In these two examples, Black individuals are being centered when, for far too long, we’ve been excluded from both outdoor spaces and the general notion of “adventure.” There are too many affinity groups and resources to list here (that’s a good thing!), so I encourage you to find a group that speaks to you, but some of the organizations I support are Blackpackers, Fat Girls Hiking, Latino Outdoors, Native Women’s Wilderness, and Muslim Hikers. There’s a space for you no matter what your identity is.

In the meantime, check out Inclusive Guide’s social media and blog, as well as all of KWEEN WERK’s channels, to follow me on my Liberation Tour throughout the South and Midwest. We’ll be sharing educational posts and videos related to Black travel over the course of my two-week trip. I also plan on using Inclusive Guide in real time so that you can see and learn about some of the inclusive places I visit. While this trip is ultimately a bonding experience for my family—and some well-deserved R&R for myself—I hope my journey increases the visibility of Black people in outdoor spaces and the world of travel more broadly. We be trippin’, y’all—we always have been. If you’ve been wanting to embark on an adventure but are worried that you won’t belong or that it isn’t for you, let me be the first to say that you 100%, absolutely can. Traveling is for everybody—and we’re taking it back. In celebration of black history month meet 15 inspiring black leaders in the Colorado's environmental and outdoor movement. These leaders are igniting lasting change in their communities and beyond. From trail runners to environmental justice activists, black people are making a huge impact in the environmental movement. Celebrate Black History Month any time of year by taking a closer look at some notable black environmentalists and outdoor leaders working in Colorado today. CRYSTAL EGLICOLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE

C. PARKER MCMULLEN BUSHMAN Colorado State University / ECOINCLUSIVE/ KWEEN Werk

KWEEN WERK is dedicated to disrupting the narrative that only able-bodied people from dominate culture care about the environment and participate in outdoor recreation activities. KWEEN stands for Keep Widening Environmental Engagement Narratives. KWEEN WERK challenges traditional representations of what it means to be outdoorsy by showing a variety of bodies engaged in outdoor spaces. Summit for Action. is a gathering for thought-provoking discussions and solutions-based recommendations for Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Nonprofit Organizations. Summit for Action brings together leaders and key stakeholders and will features a mix of planned and open space conference sessions intended to help organizations build diverse workplaces and increase community impact. Ecoinclusive Website Facebook KWEEN WERK Website Facebook Instagram Summit for Action Website Facebook JASON SWANN RISING ROUTES

Rising Routes is aiming to normalize uncomfortable conversations around social justice, diversity, equity, inclusion, and mental health, to lift the veil of “normal” and disempower stigmas and perceptions, erasive and appropriative history, and empower a future of people capable of celebrating and finding strength in their differences while working to affect sweeping systemic change. Working across cultures and identities requires us to expand our comfort zone, owning our power and privilege, and engaging in active self-reflection that interrogates what we hold to be true. The outdoors is their medium, the trail is their guide. Instagram - Rising Routes Facebook - Rising Routes Meetup.com - Https://www.meetup.com/Rising-Routes/ PATRICIA ANN CAMERON BLACKPACKERS

TAISHYA ADAMS COLORADO PARKS AND WILDLIFE COMMISSIONER/ OUTDOOR AFRO/ AMERICAN INSTITUTES FOR RESEARCH

Previously, Taishya worked with the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, the DC Public Charter Schools Board, Global Classrooms Washington, DC, and the Children Defense Fund Freedom Schools. Taishya also co-founded New Legacy Charter School – a public charter high school and early learning center for teen parents and their children in Aurora, Colorado. Taishya holds a MA in International Education from George Washington University and a BA from Vassar College. You will find her on the trail, slopes, crag, yoga mat, conference room, garden, and in the presence of those who love and cherish life. @ taishyasky KRISTE PEOPLESBLACK WOMEN'S ALLIANCE OF DENVER / LIFES2SHORTFITNESS / CITYWILD / WOMEN'S WILDERNESS

MISHA CHARLESAMERICAN ALPINE CLUB / OUTDOOR AFRO

LEANDER R. LACY LACY CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC

Leander went on to work 8 years with The Nature Conservancy. His final role before starting his own business was as the Global Methodology Learning Coordinator where he assisted teams throughout the world with strategic planning on large-scale conservation issues and ensuring that social science principles were incorporated. Now he takes his extensive experience and is helping environmental organizations accomplish their goals in innovative and people-focused ways. He recently facilitated a strategic planning process for a 5-state collaborative to save the Southern U.S. shortgrass prairie, he is helping an organization understand their need for diversity, equity, and inclusion in their North America agriculture approach, and recently his company became international as he was sought out by a conservation group in the Bahamas to conduct focus groups to understand and begin mending the breakdown in trust between fishers, law enforcement, and conservation groups. www.lacyconsultingservices.com Find his organization on Facebook and LinkedIn KRISTINA OPRE GRAYENVIRONMENTAL LEARNING FOR KIDS (ELK)

SID WILSONA PRIVATE GUIDE, INC.

Sid Wilson’s has made large contributions to the outdoor tourism industry. Sid revels in sharing with clients the inspiring tales of Colorado's early pioneers whose resourcefulness enabled them to survive and prosper in the Rocky Mountain's volatile "boom" and "bust" economic cycles of the past. Sid is very active in his community. He has served as a Past Chairman of the Board of directors for the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center; Director Emeritus for the Center of the American West, @ CU Boulder; member board of directors for Colorado Historical Society’s African American Advisory Council; past board member and vice-chair of Historic Denver; past member of Historic Preservation State Review Board; Founding member and past Board Chairman of the James P. Beckwourth Mountain Club; Commissioner for Denver Mayor’s African American Commission; former member board of directors Colorado Scholarship Coalition; member board of directors Denver Zoological Foundation; Current member and past Board of Directors Chairman of both Lincoln Hills Cares, and Lincoln Hills Cares Foundation, and as an instructor for the International Guide Academy / USA & Mexico. JESSICA "JESS" NEWTONVIBE TRIBE ADVENTURE

MONTICUE CONNALLYJIRIDON APOTHECARY

Website: JiridonApothecary.com Instagram: @a_root_aw8kening Facebook: Monticue Connally Patreon: Patreon.com/arootawakening ANDREA DANCY AUGUISTE NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION

TASHMESIA MITCHELLcityWILD, MY OUTDOOR COLORADO COLE COALITION, PROJECT BELAY

KIA M. RUIZRIGHT TO KNOW/ GIRL TREK/ MEOW WOLF

When the environment does not have intrinsic value to be held sacred Kia approaches ways people can connect with it through economic and consumer impacts these days. Her passion is in connecting people to their interdependency with themselves, each other, and the environment. The yoga teaching is a tool to balance her brain and elevate others with how they show up in the world. She has been teaching for over ten years with specialities in prenatal, postpartum. yoga for healing, corporate, and hatha where she is now also a teacher trainer. Kia volunteers with Girl Trek as an Adventure Squad Leader. Girl Trek is the nation’s largest public health non-profit serving Black women. She has trained with the Sierra Club as a Hike Leader to support how people get on the trails at the annual Stress Protest and around the greater Denver area. You can find Kia on instagram at @kiamruiz where she posts about getting outside, her Denver life with her family, food, and how these all tie into to her personal thread of interdependency and connection. @kiamruiz

This morning I am reminded of one of my favorite poems "A small needful fact." It sits at an intersection for me. An important reminder of the crossroads between environmentalism, environmental justice, and social justice issues. Eric Garner who had asthma, was among those people of color who often face higher exposure to pollutants and who often experience greater responses to such pollution through disease and health issues. We cannot deny this intersection. To truly address environmental issues that impact us all we have to address the social issues that impact some of us more.

Many people will only know of Eric Garner as the man who died in a police choke-hold in 2014. But I like to think of him as a gardener. I hope you enjoy the poem. ____________________________________ A small needful fact By Ross Gay Is that Eric Garner worked for some time for the Parks and Rec. Horticultural Department, which means, perhaps, that with his very large hands, perhaps, in all likelihood, he put gently into the earth some plants which, most likely, some of them, in all likelihood, continue to grow, continue to do what such plants do, like house and feed small and necessary creatures, like being pleasant to touch and smell, like converting sunlight into food, like making it easier for us to breathe. The sun may shine indiscriminately but studies show that children of color deal with the effects of pollution a disproportionate amount. We believe all have the right to clean air, water and land. To address these inequities we have to begin with education. Privilege is often invisible to those that hold it. So educating ourselves and those in our network about the disparities that exists is important.We must define environmental justice in our organizations. We must understand how environmental justice affects air and water quality and the health of communities we partner with. If you want to learn more here are some resources: Environmental justice, explained https://youtu.be/dREtXUij6_c We can’t truly protect the environment unless we tackle social justice issues, too https://www.popsci.com/environmentalism-inclusive-justice… Air Pollution, Asthma, and Children of Color http://www.berkeleywellness.com/…/air-pollution-asthma-and-…. Study finds a race gap in air pollution — whites largely cause it; blacks and Hispanics breathe it https://amp.usatoday.com/amp/3130783002 |

KWEEN WERK NARRATIVESKWEEN stands for Keep Widening Environmental Engagement Narratives. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed